- Home

- Mackenzie Phillips

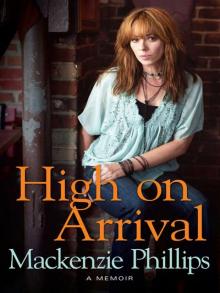

High On Arrival

High On Arrival Read online

HIGH ON ARRIVAL

HIGH ON ARRIVAL

MACKENZIE PHILLIPS

with HILARY LIFTIN

Simon Spotlight Entertainment

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2009 by Shane’s Mom Inc.

NOTE TO READERS

The names and identifying details of some individuals portrayed in this book have been changed.

Music Permissions:

“She’s Just 14” (John Phillips) published by Phillips-Tucker Music—from the John Phillips album “Pussycat” (2008 Varese Sarabande Records).

“If King Can Can, Who Can’t? (My Name is Can)” (John Phillips) published by Phillips-Tucker Music—from the John Phillips album “Andy Warhol Presents Man On the Moon” (2009 Varese Sarabande Records).

“Wee Funkie Little Bats” (John Phillips) published by Phillips-Tucker Music— from the John Phillips album “Andy Warhol Presents Man On the Moon” (2009 Varese Sarabande Records).

“I Miss You” Copyright 2001, Welsh Witch Music, EMI Virgin Music, INC, Future Furniture Music. All rights on behalf of Welsh Witch Music administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Photography credits:

(top): CBS/Landov; (top), (top and bottom), (top):

Suzanne L. Sinenberg; (bottom): Neal Preston.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form whatsover. For information

address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Simon Spotlight Entertainment hardcover edition September 2009

SIMON SPOTLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT and colophon are

trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at

1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors

to your live event. For more information or to book an

event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at

1-866-248-3049 or visit our website as www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Jaime Putorti

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4391-5385-7

ISBN 978-1-4391-5757-2 (ebook)

For Shane—

Love. Love. Love.

R.I.P. Max

January 15, 2001—June 3, 2009

She’s just fourteen

Little movie star queen

There isn’t much

She hasn’t seen

She’s ridden in limousine cars

Dated pop stars with rainbow hair

She says that’s nowhere

She always says

I’m just a sexy trashcan

But she’s just a little girl

Who thinks like a man

Sometimes her daddy spoiled her

Sometimes he treated her rough

Sometimes she’s gentle

Sometimes that chick she’s tough

But she’s always too nice to the driver

She says, James have you had your supper?

She’s always too high on arrival

She runs on her high platform heels

She falls flat on her face

She knows how life feels

And she’s just fourteen

—From “She’s Just 14” by John Phillips

Contents

Introduction

Part One: Laura Phillips

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part Two: Mackenzie Phillips

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part Three: Girlfriend, Wife, Daughter

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Part Four: Papa's New Mama

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Part Five: The Rock

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

AFTERWORD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

PHILLIPS, LAURA MACKENZIE

In the mideighties, when I was on tour with the New Mamas & the Papas, a porter brought two packages up to my hotel room. One contained a book, my father’s newly published memoir, but I was more interested in the other package—a flat FedEx letter containing an eighth of an ounce of cocaine.

The band, a reconstituted version of the Mamas & the Papas, included my father, Denny Doherty, Spanky McFarlane, and me. We were on an extended tour, performing in city after city for more than 250 days of the year. In each city, a FedEx like the one I was holding awaited me, and I spent all day every day in my hotel room, shooting up coke, coming out only to appear onstage for the nightly gig. Then I’d return to my hotel and do more coke. I was twenty-six years old.

I put Dad’s book aside, opened the FedEx, and prepared a shot. Using a scarf, I tied off my arm. As I looked for a vein, I felt the familiar rush that accompanied the ritual itself. I knew what was coming. I pushed the needle in. As the coke entered my bloodstream I felt a euphoric onrush of sensation. I was back where I wanted to be.

Only then did I pick up my father’s book. Papa John: A Music Legend’s Shattering Journey Through Sex, Drugs, and Rock ’n’ Roll was a brick of a book with the title faux spray-painted on the jacket in neon colors. I turned it over in my hands to look at the photo of my father on the back. He was clean-shaven and smiling a newscaster smile, the sanitized, post-rehab version of my father. He didn’t look remotely like his hipster self.

Then I flipped to the index and looked to see if I was in it. There I was: “Phillips, Laura Mackenzie.” Under my name was a list of subheadings and page numbers. I scanned down the entries:

Phillips, Laura Mackenzie

acting career of …

arrested on drug charges …

attempts to clean out …

in California …

childhood of …

drug use by …

early childhood of …

at finishing school in Switzerland …

Jeff Sessler and …

marriage to Jeff Sessler …

Peter Asher and …

rape …

shipboard romance on QE 2 …

There it was, my life to date, with highlights selected, cross-referenced, and alphabetized. I had been organized and reduced to a list of sensational and mostly regrettable and/or humiliating anecdotes. Being indexed, particularly under such dubious headings, gave me a weird feeling that definitely wasn’t pride. I felt like I wasn’t a real person, just a list of incidents and accidents. Whoever compiled that index—I’m pretty sure my father wasn’t up to such a mundane and detailed task—was just doing his or her job, but it was cruelly reductive.

&

nbsp; Decades passed before I thought about that index again. In 2008, now nearly fifty years old, I found myself in a police station in the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles. I was sitting in a hallway on a bench. My hands were cuffed and the handcuffs were hooked to the bench. All the cops were staring at me: the middle-aged lady, the former child star, who had just been busted at the airport for heroin possession. A low, low moment.

How had I gotten myself here? Was this happening? The best and worst moments of my life have always felt surreal, as if the events were just another entry in that foreign index someone else created. But the cuffs cut into my hands with the cold rigidity of reality. I’d been addicted to drugs before, and I’d overcome my addiction. That was fifteen years ago, so many long, mostly happy, entirely drug-free years. I never thought I would relapse. I’d been clean for so long that I thought I was fixed. But if the addiction was a cancer that had been carefully excised, well, I’d missed a spot. It had grown back, all the more fierce and malignant. Here I was again. Back at the bottom, caught in the arms of a bad-news lover I thought I had dumped for good. I could envision the new entry in the index, typed in the same font. Chronologically, it belonged right below “happy working mother.” It would say, “second arrest on drug charges,” a one-line condemnation that only hinted at everything that had led me to that bench.

All my life I’ve been a person who starts things and can’t finish them. As a junkie, as an actress and musician, as a mother— it’s been hard for me to complete even the simplest cycles of action. Like using one tube of toothpaste from beginning to end before buying the next. I’d inevitably leave it in a hotel, or lose track of it for long enough that I’d have to open another tube, then rediscover the original—half the time, at best. Sitting on that bench, looking ahead, I knew that in some way I had to go back. I had to go back fifteen years, to all the work I’d done when I got sober, to the surgery that had sent me into remission for so long. I had to see what was left unfinished.

In a way, the surreal feeling is a shield. I have demons, haunted parts of my life and myself that are painful and scary. Facing them, revealing them, makes them too real. But I think about the index of my father’s book, and how it reduced me to highlights and lowlights. I think about my mug shot in the tabloids. And I think of all that happened before, between, and after. The rest of the story. It is time to sort out a life that too often I left blurry, unprocessed, unreal, hoping that in doing so I would be leaving it behind me forever. It is time for me to return to that life, to face it, explain it, accept it, and let it rest as the insane, fun, ridiculous, terrifying, and true sequence that led a bright, goofy, famous little girl to a bleak jail bench, and I want to do it right, so that it is real and whole, and I in turn become real and whole.

I’m nearly twice as old as I was when my father’s book came out, and though this is my story, not my father’s, my relationship with him is undeniably central to my life. Dad was the great and terrible sun around which his children, wives, girlfriends, fellow musicians, and drug dealers orbited, relentlessly drawn to his fierce, inspiring, damaging light. The alternate solar system my dad drew me into had hilarious moments—like sliding down the banisters of my dad’s Malibu mansion with Donovan—and portentous scenes, like when I tried cocaine for the first time at the age of eleven. There are happy memories of the stable work and family I found on One Day at a Time. There are loving and painful memories of the fucked-up family I wouldn’t trade for the world. There are lost memories—conversations and chronologies I wish I could remember—and events I know my whole being wants to erase forever. There was a father-daughter relationship that crossed the boundaries of love to break many taboos, as my father was wont to do. My life was one of a kind—not everyone has a rock-star father, childhood stardom, and enough money and fame before the age of sixteen to last a lifetime. I have had more than my share of highs and lows. But all of it happened, it’s real, and it’s who I am.

PART ONE

LAURA PHILLIPS

1

Our condo: a perfectly nice place to live. My mother kept an orderly, clean house. She drove us to school every day and cooked dinner every night. She was a proper lady, the kind of woman who never wore white after Labor Day, crossed her legs at the ankle, and expected her children to be well mannered and respectful. We said please and thank you. We never let the screen door slam. We knew how to set a dinner table. My mother was sweet and warm, and she knew how to make life fun for my brother Jeffrey and me even if there wasn’t much money. She’d buy a bunch of beads and we’d sit by the fire making necklaces. We’d cover the kitchen table with newspaper and have crab legs like we used to when we lived in Virginia. There was laughing, singing, dancing, and playing dress-up. At bedtime, she cuddled me, held me, called me Laurabelle, my little snowflake, my baby girl. These are the things that a mother does, and we expected them. Five days a week. But when Friday rolled around, everything changed.

Weekends, we entered another world. My dad, John Phillips, was a rock star, the leader and songwriter of the Mamas & the Papas. The Mamas & the Papas were huge in 1966. Their first album had just come out, and it was the number one album on the Billboard 200. Money poured in from hits like “Monday, Monday” and “California Dreamin’.” Dad was fabulously rich and famous.

After school on Friday, a cavernous Fleetwood limo would glide down our street in Tarzana, a suburban neighborhood in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley. The limo would roll to a stop in front of our condo complex. I was six years old and my brother was seven. The neighborhood children would make thrones out of their hands and carry us to the car. As we climbed in, the kids would peer in the windows, hoping to get a glimpse of our father. He was never in the car. The engine purred, and we slid out of reality. The limo would transport us to either Dad’s mansion in Bel Air or his mansion in the Malibu Colony, where our relatively stable childhood veered down a psychopharma rabbit hole.

I was conceived during a short reconciliation between my parents. As a little girl I hardly lived with my father. My dad had ditched my mother for a sixteen-year-old girl named Michelle when I was two, maybe younger. In the next few years Mom began to work at the Pentagon to support the three of us—herself, my brother, and me. There wasn’t a lot of money, we lived in a small apartment in Alexandria, Virginia, and my mom dated a lot. Every Sunday we had dinner, either at my grandmother Dini’s or at my aunt Rosie’s. Meanwhile, Dad and his new wife, Michelle Phillips, became famous with the Mamas & the Papas practically overnight and lived a recklessly extravagant life.

Dad and Michelle made their home in Los Angeles, and eventually my mother moved there too, so now my parents were living in the same city, but in different worlds. Dad and Michelle’s life felt like a fairy tale. She was beautiful and so young, the quintessential California girl. Dad was almost six foot six and dressed in handmade floor-length caftans and the like. He looked … like Jesus in tie-dye. On weekends Michelle took me clothes shopping at Bambola in Beverly Hills. She bought me tiny kid gloves in all different colors, dresses with matching coats, ankle socks, and Mary Janes. This alone was enough to make a princess out of me, but the dichotomy between my parents’ lives was far bigger than being spoiled with clothes by Michelle. As soon as we drove through the massive wrought-iron gate of Bel Air, the contrast was mind-boggling. We were special. We were royalty.

My father was always surrounded by a noisy, outrageous, wild party. Rock ’n’ roll stars, aristocracy, and Hollywood trash streamed in and out of his homes. He lived beyond his means. There were eight Rolls-Royces in the driveway and two Ferraris. The house was full of priceless antiques, but if something broke, it never got fixed. The housekeeper hadn’t been paid, or she was fucking my father. There was a cook, but nobody shopped for food. The house was complete chaos, a bizarre mix of excess and oblivion, luxury and incompetence. I swam naked at midnight in the pool or the ocean and scrounged for dinner. I chased the pet peacocks around the estate grounds and had no idea what I might hear

or see on any given night.

At the house in Bel Air my brother and I shared a room with twin beds. One night we awoke to hear Dad and Michelle making some kind of ruckus. It surpassed the everyday level of ruckus, so we sat up in bed and started calling for them, “Hey! What’s going on?”

Michelle came into the room. She said, “Don’t worry, your father and I were just playing.” She was carrying a long stick with metal stubs poking out of it. Jeffrey and I looked at each other. This was no innocent game of Monopoly. Years later I channel-surfed past a show about cowboys and recognized the weird stick Michelle had been holding that night. It was a cattle prod. They were chasing each other around with a cattle prod. That may have been an isolated bizarre incident. But life then seemed to be nothing but a long, continuous series of isolated bizarre incidents, so much weirdness every day that the weirdness became everyday.

The Mamas & the Papas played the Hollywood Bowl, a famous amphitheater smack in the middle of Hollywood. It was the Mamas & the Papas’ first formal live gig. Michelle decided to commemorate the event by piercing my ears. I was seven years old, compliant—a perfect dress-up doll for Michelle. She sat me on the bedroom floor and gathered a sewing needle, pink thread, ice, and a wine cork. Holding the wine cork behind my ear to protect my neck, she forced the threaded needle through my ear, and then tied little peacock feathers (from the pet peacocks) to the ends of the pink threads. Michelle had assembled her tools so thoughtfully and executed the procedure so calmly—which was even more impressive when I later found out she was on acid at the time.

High On Arrival

High On Arrival